1.1.1. Satellite Earth’s outgoing longwave and shortwave radiation budget intercomparison for climate monitoring#

Production date: 11-06-2025

Produced by: CNR-ISMAR, Andrea Storto, Vincenzo de Toma

🌍 Use case: Consistency assessment of Earth Radiation Budget products#

❓ Quality assessment question(s)#

How consistent are the Earth Radiation Budget products provided by C3S?

The Earth Radiation Budget (ERB) Outgoing Longwave Radiation (OLR) and Outgoing Shortwave Radiation (OSR) products allow quantifying outgoing longwave and shortwave radiation, respectively, which are in turn important for several climate applications. In particular, a non-exhaustive list of possible applications include: i) evaluation and potential improvement of climate models, through routinely validation of CMIP individual simulations and ensembles against OLR and OSR data, allowing to assess the net radiative forcing and possibly leading to improved configurations through re-tuning of e.g. aerosol-cloud interactions, radiative transfer schemes, etc.; ii) tracking the Earth’s Energy Imbalance (EEI), which consists of long-term mean imbalance of incoming and outgoing energy at the top-of-the-atmosphere (TOA). This imbalance is mostly accumulated into the oceans, and its analysis is crucial to monitor recent global warming; iii) diagnosing El-Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and other climate variability modes, which are intimately linked to anomalies of OLR (e.g. enhanced convection); iv) analyse cloud radiative effects (e.g. in combination with clear-sky radiative data) and their impact on climatic changes; and many more. However, their temporal coverage and spatial detail varies across the ERB products. Over the overlapping periods, the products are in good agreement, except for the OLR at high latitudes (e.g. north of 60*N / south of 60°S), while discrepancies in OSR arise at both mid- (generally less than 10 W m-2) and high-latitudes.

📢 Quality assessment statement#

These are the key outcomes of this assessment

The OLR/OSR products capture the spatial and temporal variability of the outgoing longwave radiation / outgoing shortwave radiation (at the top of the atmosphere) for use in climate analyses, climate model evaluations, and radiative forcing studies.

The ERB OLR/OSR products have different temporal coverage and spatial resolution, namely their combined use is not straightforward and it is recommended for advanced users only, or for selected periods.

The consistency between the products concerning spatially averaged values is generally acceptable. Climatological maps and zonally averaged values indicate that the products are sufficiently consistent in most areas, although differences exist and tend to increase near the polar regions.

The estimation of outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) at the top of the atmosphere is crucial for understanding the Earth’s radiation budget (ERB), which plays a significant role in climate dynamics and energy balance. Despite its importance, accurately assessing OLR-ERB variability using remote sensing data and satellite missions is fraught with challenges due to calibration inconsistencies, data gaps, and the complex interactions of radiation with atmospheric constituents ([1]; [2]; [3]; [4]).

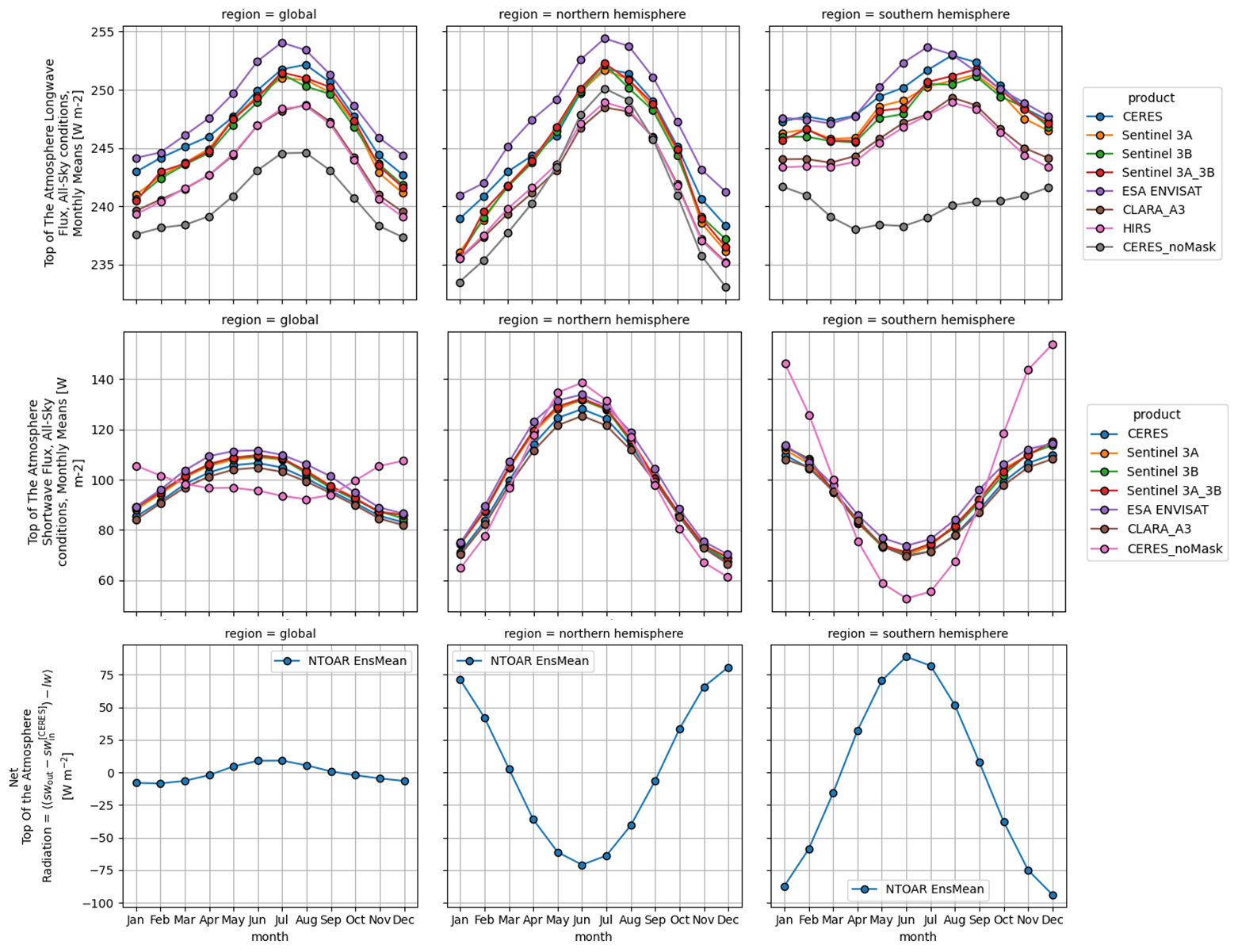

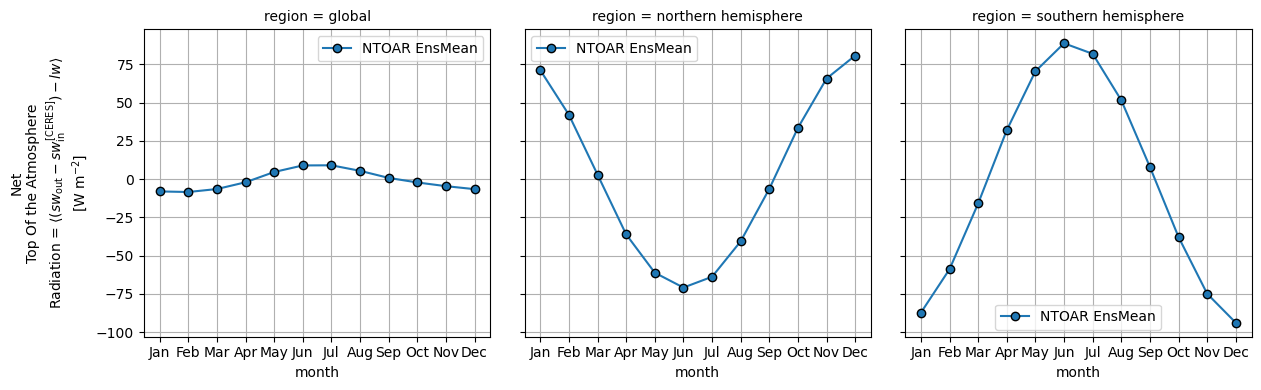

Fig. 1.1.1.1 Monthly mean time series of OLR (first row), OSR (second row) Ensemble mean Net Top Of the Atmosphere Radiation (NTOAR) (third row) for different geographical regions (columns).#

📋 Methodology#

In this notebook we inter-compare the following Earth Radiation Budget Products, available through the Climate Data Store (CDS) by C3S:

CERES Energy Balanced and Filled (EBAF) TOA Monthly means data in netCDF Edition4.1. NASA Langley Atmospheric Science Data Center DAAC (NASA CERES EBAF)

NOAA CDR Program, (2018): NOAA Climate Data Record (CDR) of Monthly Outgoing Longwave Radiation (OLR), Version 2.7 (NOAA/NCEI HIRS).

Earth’s radiation budget from 1979 to present derived from satellite observations. CCI ICDR product version 3.1. Copernicus Climate Change Service Climate Data Store (C3S CCI).

ESA Cloud Climate Change Initiative (ESA Cloud_cci) data: Cloud_cci ATSR2-AATSR L3C/L3U CLD_PRODUCTS v3.0 (ESA Cloud CCI).

CERES is the only product which gives also the incoming shortwave radiation: thus, in order to evaluate the Net Top Of the Atmosphere Radiation, the ensemble mean budget was built using outgoing longwave and outgoing shortwave from each product, and the incoming shortwave from CERES, and then averaging across the product dimension.

The analysis and results are organised in the following steps, which are detailed in the sections below:

1. Choose the data to use and setup code

📈 Analysis and results#

1. Choose the data to use and setup code#

In this section, we import the required packages and set up the dataset names for further use in the following sections. Processing functions are also defined. We select only complete years available for each dataset in order to have a fair comparison between different products.

2. Download and transform#

The code below will download the products. Notice the definition of common periods for the different products, and their inclusion in the mean map dictionary. When the variable to download is the shortwave component, we skip the HIRS dataset, since only longwave is available within it.

3. Plot spatial weighted time series#

Below, we calculate and plot spatially weighted means for the different earth radiation budget products, in terms of montly climatologies, although the sampling period of each dataset is, in general, different from the others (i.e. CERES: 2001-2023, Sentinel 3A: 2017-2021, Sentinel 3B: 2019-2021, Sentinel 3A_3B: 2019-2021, ESA_Envisat: 2003-2011, CLARA_A3: 1979-2020, HIRS: 1979-2023, CERES_noMask: 2001-2023). Despite each dataset has a different length, we want here to inspect how the different products reproduce the seasonal cycle, both for the global mean, and for each hemisphere. Notice we also used the non-masked version of CERES (CERES_noMask), for two reasons: fist, we want to have an idea of what is the main effect of the masking (i.e. if it affects mainly the northern and southern hemisphere), and second to have the possibility of giving the best possible estimate of the Net Top of the Atmosphere Radiation (i.e. as much as possible close to a sort of Earth Energy Imbalance).

The pronounced seasonality in OLR is mostly linked with the larger land area in the Northern Hemisphere, while that one in OSR linked with the solar cycle.

The offsets are greater in OLR than in OSR, with the ESA product (ENVISAT) being positively biased compared to the other products.

Most satellite datasets available from the Climate Data Store (CDS), such as those from the CLARA or HIRS record, are not gap-filled and do not always provide full global coverage. Therefore, they cannot be directly used to compute global EEI without additional assumptions, spatial extrapolation, or fusion with other datasets. Here, CERES-EBAF is referenced as a benchmark for EEI estimation, but the datasets from the CDS are not used to compute EEI directly, since they do not currently support a comparable global radiative balance analysis. Still, it is possible to look at the Imbalance annual cycles for the Net Top Of the Atmosphere Radiation, which is shown below. Specifically, NTOAR is calculated for each of the datasets in this notebook as the difference between the net shortwave and net longwave component, but calculating the net shortwave using always the incoming component from CERES-EBAF. In the end, the mean across product is extracted, constituting a sort of Ensemble mean.

Next, we show the Net Top Of the Atmosphere Radiation annual cycle for the whole available domain (with masking and regridding), and for the Northern and Southern Hemisphere. The EEI is the small difference between the sunlight the Earth absorbs and the thermal (longwave) plus reflected (shortwave) radiation it emits, and represents a fundamental “engine” of climate change. Even a tiny positive imbalance (on the order of 0.5-1 W m-2, according to recent estimates [13]) sustained year after year is what drives ocean heat uptake, ice melt, sea-level rise and ultimately the global temperature increase we observe.

The global average of Net Top Of the Atmosphere Radiation indicates a small seasonal cycle (about 15 W m-2 peak-to-peak) compared to hemispheric averages, with a slight maximum Net Top Of the Atmosphere Radiation in June-July. That means mid-year the Earth is absorbing just a bit more energy than at other times, largely because Northern Hemisphere land is warm, and snow-free.

4. Plot time weighted means#

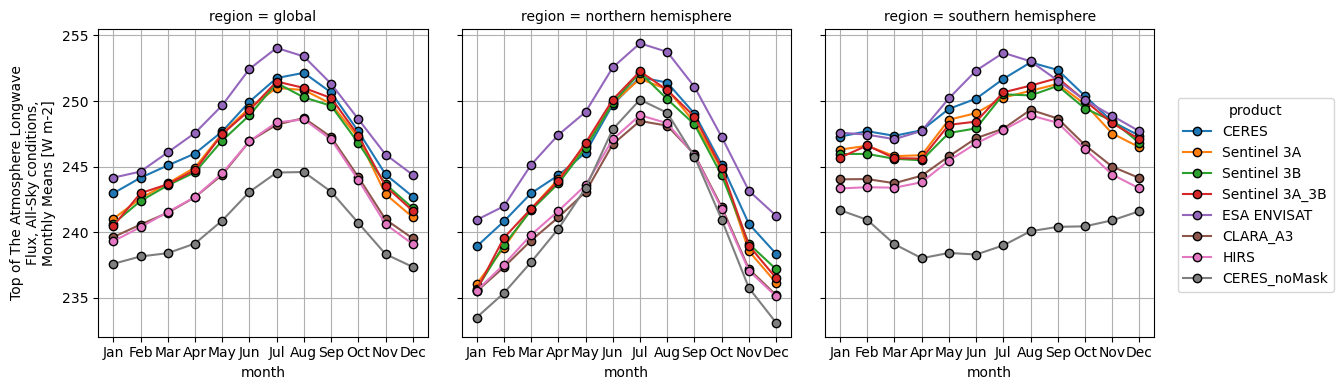

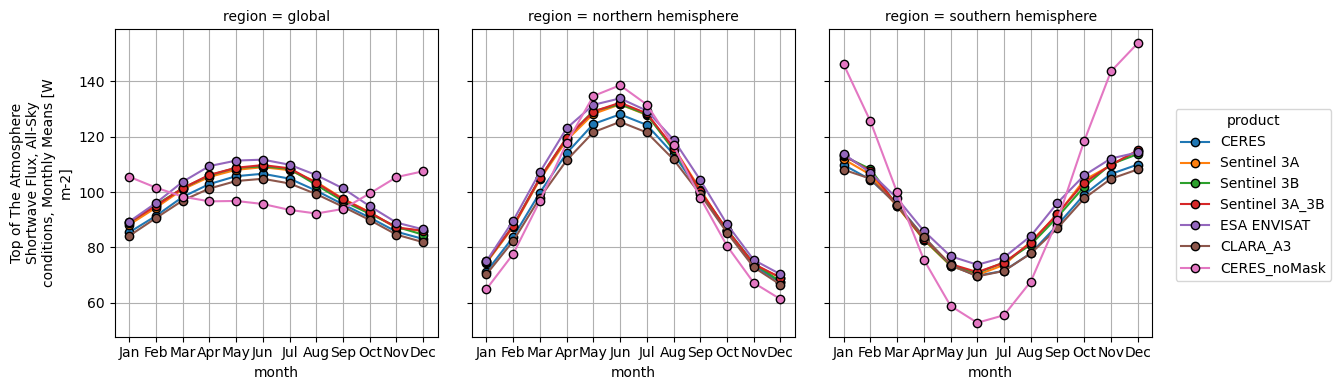

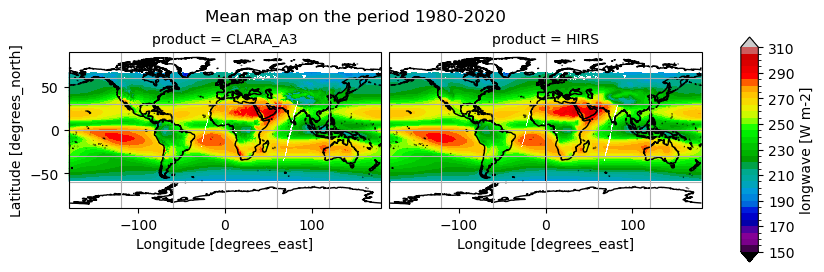

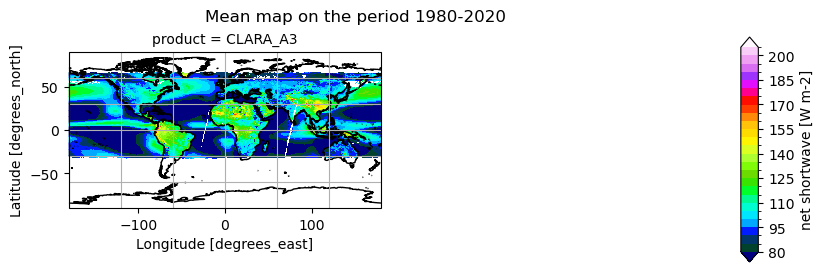

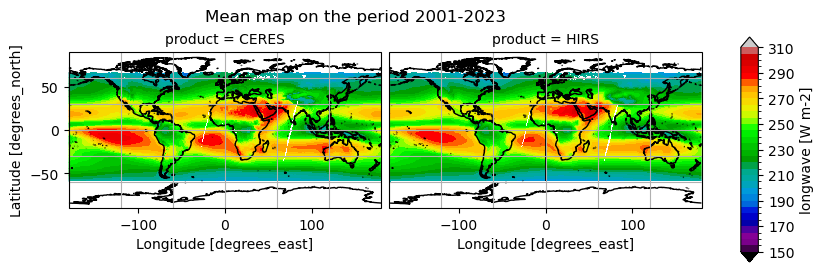

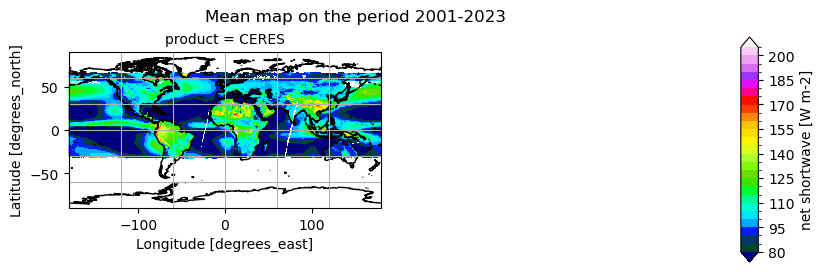

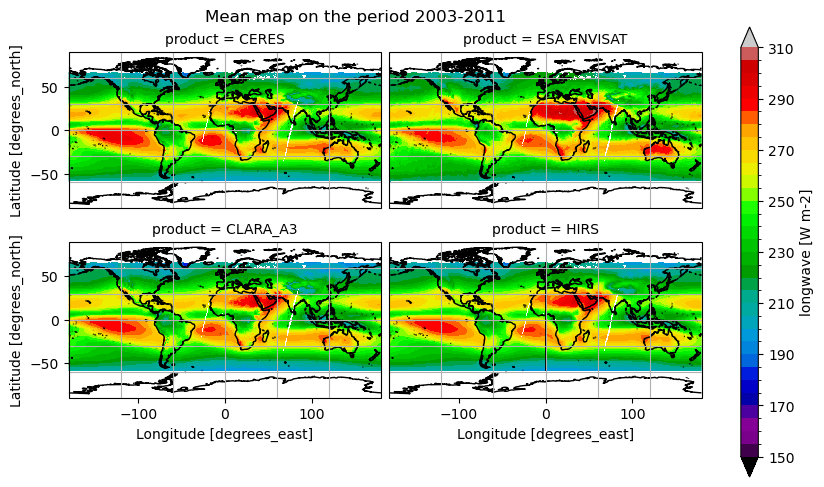

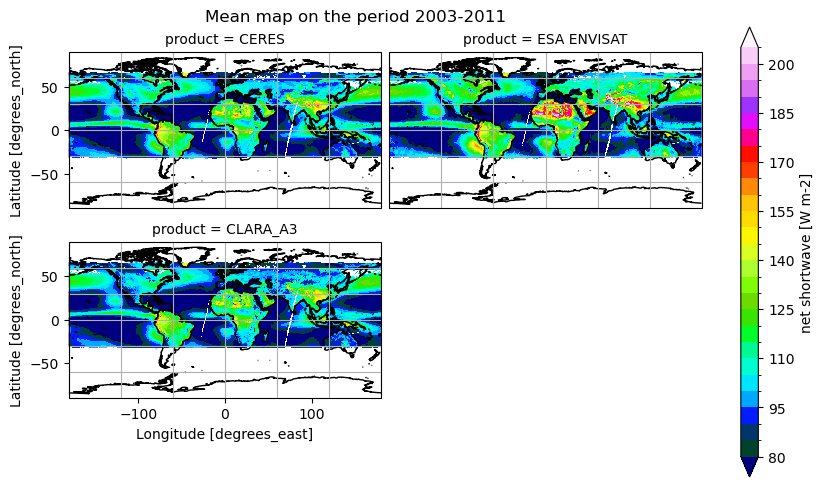

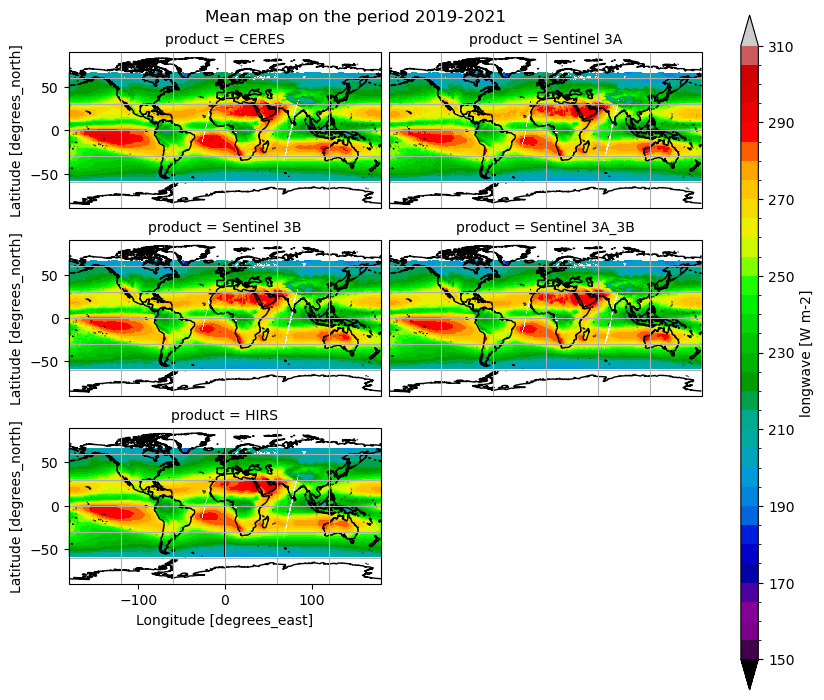

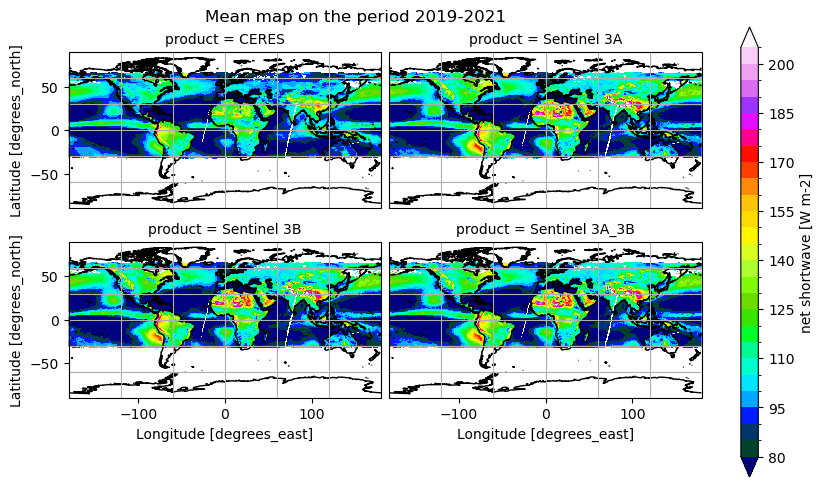

Below, we calculate and plot time-weighted means for the different radiation budget products. Please note that different periods were considered, in order to make fair comparison between products wich have a different temporal extent.

Time mean spatial maps show consistent spatial features across the products, although with large offsets and difference (e.g. near the Equator, at high latitudes). Differences are also due to varying spatial resolution, and different temporal and spatial sampling across the products.

All products show highest OLR over the subtropical deserts (e.g. Sahara, Arabian Peninsula, central Australia) and clear‐skies over the eastern subtropical ocean gyres, and lowest OLR where deep convection occurs (ITCZ, tropical rainforests) and at high latitudes under clouds. All OLR products agree on the major “warm” desert maxima and “cold” convective minima. Differences are very small (<5 W m-2) in the well‐sampled tropical belt; HIRS can show a bit more structure in the Intertropical Convergence Zone (likely due to higher spectral resolution), whereas the other products tend to smooth the strongest minima and maxima slightly. Concerning the OSR, all products feature bright subtropical desert maxima (200–220 W m-2), low OSR (80–100 W m-2) in persistently cloudy regions (ITCZ, midlatitude storm tracks, equatorial Pacific), and moderate values (120–160 W m-2) over clear‐sky oceans. The spatial patterns are remarkably consistent across the products, with differences generally of the order of less than 4 W m-2.

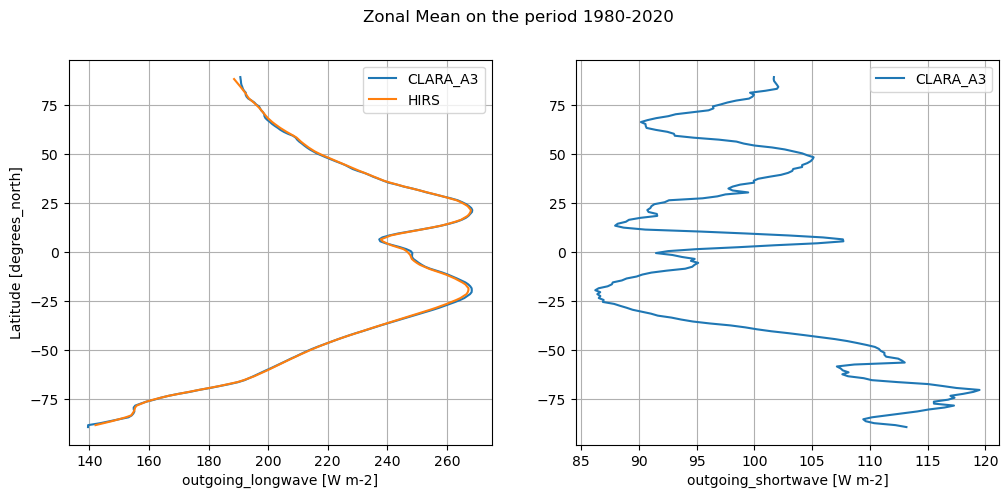

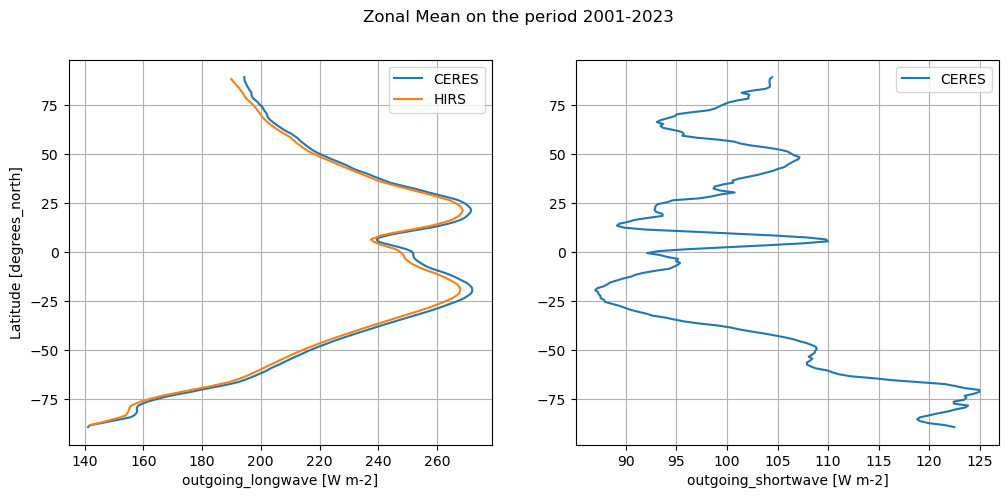

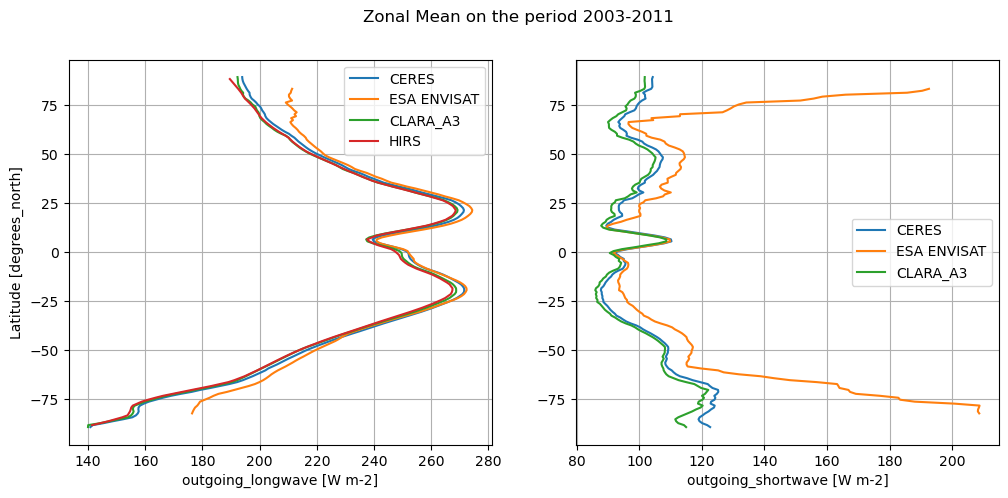

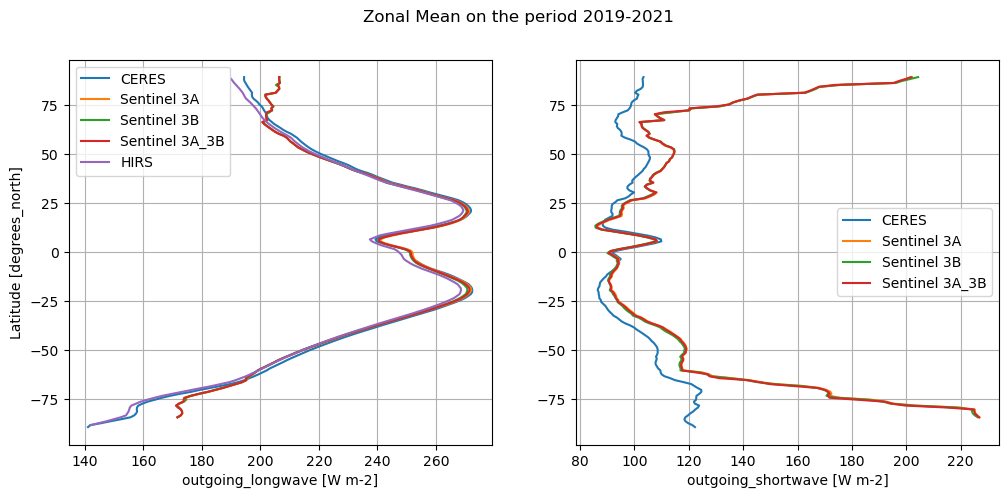

5. Plot spatial weighted zonal means#

The code below will calculate and plot weighted zonal means for the radiation budget products. For the sake of comparison, different periods are shown consistently with different temporal overlapping windows.

Zonal averages indicate the good consistency among the products, except at thig latitudes (e.g., south of 50°S and north of 50°N). In particular, CERES and ESA ENVISAT show good agreement in the OLR, with CLARA_A3 and HIRS possibly deviating slightly, especially at higher latitudes. Also, OSR shows the largest discrepancies going poleward, which may arise from differences in cloud detection or albedo algorithms.

Discussion and applications#

The differences identified across the OLR and OSR datasets primarily reflect known characteristics of the satellite instruments and retrieval algorithms from which the various climate data records are constructed. For OLR, the spread between the CERES EBAF record and the HIRS and CLARA-A3 products is consistent with the long-recognized sensitivity of longwave flux retrievals to spectral sampling, cloud detection, and scene-dependent angular corrections ([1], [4], [5]). CERES derives broadband fluxes using detailed angular-distribution models (ADMs) developed specifically for top-of-atmosphere applications [3], which typically results in smaller biases in cloudy and high-latitude regions. In contrast, HIRS and the AVHRR-based CLARA-A3 rely on narrower channels and empirical regressions to estimate broadband longwave radiation, a known source of latitudinal and surface-type–dependent discrepancies documented in their validation reports (HIRS PVR, CLARA-A3 PVR). These differences help explain the stronger gradients observed in the CLARA-A3 OLR fields and the slight warm-scene bias in HIRS over subtropical dry regions.

The Sentinel-3 SLSTR (3A, 3B, and the merged 3A+3B) interim CDRs show overall good consistency with the CERES reference but display enhanced variability in the tropics and over land surfaces. This behaviour is in line with their validation documentation, which highlights sensitivity to cloud screening and to the limited temporal extent of the interim SLSTR record relative to multi-decadal products (CERES Quality Summary, Sentinel Quality Assurance Document). The relatively short data period (2017–2021) also means that interannual variability associated with ENSO events—known to modulate tropical OLR [7]—can disproportionately influence the mean differences when compared to long records such as CERES or HIRS.

For OSR, discrepancies among products similarly reflect differences in sensor spectral coverage, calibration stability in the visible and near-infrared, and the treatment of anisotropy in the shortwave domain. CERES shortwave fluxes benefit from scene-dependent ADMs and long-term calibration stability [1], [4], [9], which contributes to the coherent latitudinal reflection patterns typically used as a benchmark. The CLARA-A3 product, derived from AVHRR, shows slightly higher reflected shortwave radiation in bright subtropical and high-latitude regions, consistent with known limitations in AVHRR-based angular corrections and cloud-phase retrievals noted in its product validation reports. Similarly, OSR from ESA’s ENVISAT AATSR and from SLSTR shows small but systematic differences over marine stratocumulus regions—areas where shortwave anisotropy and cloud optical properties strongly influence flux retrievals. These patterns are consistent with prior evaluations of shortwave absorption and model–observation differences [11], [12].

Overall, the magnitude and spatial structure of the inter-product differences observed here align with previously documented behaviour of broadband radiation datasets and with theoretical expectations derived from radiative-transfer and climate-feedback studies [6], [8], [10], [13]. The consistency of many features across independent retrievals—particularly the subtropical shortwave reflection maxima and the tropical longwave minima—supports the robustness of these products for climatological analyses, while the remaining discrepancies can be traced to well-understood algorithmic and instrumental differences identified in the respective validation reports.

ℹ️ If you want to know more#

Key resources#

Code libraries used:

C3S EQC custom functions,

c3s_eqc_automatic_quality_control, prepared by B-Open

References#

[1] Loeb, N. G., Wielicki, B. A., Doelling, D. R., Smith, G. L., Keyes, D. F., Kato, S., … & Wong, T. (2009). Toward optimal closure of the Earth’s top-of-atmosphere radiation budget. Journal of Climate, 22(3), 748-766

[2] Harries, J. E., Brindley, H. E., Sagoo, P. J., & Bantges, R. J. (2001). Increases in greenhouse forcing inferred from the outgoing longwave radiation spectra of the Earth in 1970 and 1997. Nature, 410(6826), 355-357.

[3] Wielicki, B. A., Barkstrom, B. R., Harrison, E. F., Lee III, R. B., Smith, G. L., & Cooper, J. E. (1996). Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System (CERES): An Earth observing system experiment. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 77(5), 853-868.

[4] Loeb, N. G., Wielicki, B. A., Su, W., Loukachine, K., Sun, W., Wong, T., … & Lin, B. (2012). Advances in understanding top-of-atmosphere radiation variability from satellite observations. Surveys in Geophysics, 33(3-4), 359-385

[5] Susskind, J., G. Molnar, L. Iredell, et al., 2012: Interannual variability of outgoing longwave radiation as observed by AIRS and CERES. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 117, D23107, doi: 10.1029/2012JD017997.

[6] Donohoe, A., Armour, K. C., Pendergrass, A. G., & Battisti, D. S. (2014). Shortwave and longwave radiative contributions to global warming under increasing CO2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(47), 16700-16705. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1412190111

[7] Su, W., N. G. Loeb, L. Liang, N. Liu, and C. Liu (2017), The El Niño–Southern Oscillation effect on tropical outgoing longwave radiation: A daytime versus nighttime perspective, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 122, 7820–7833, https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JD027002

[8] Soden, B. J., and I. M. Held, 2006: An Assessment of Climate Feedbacks in Coupled Ocean–Atmosphere Models. J. Climate, 19, 3354–3360, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI3799.1

[9] Loeb, N. G., J. M. Lyman, G. C. Johnson, R. P. Allan, D. R. Doelling, T. Wong, B. J. Soden, and G. L. Stephens, 2012: Observed changes in top-of-the-atmosphere radiation and upper-ocean heating consistent within uncertainty. Nat. Geosci., 5, 110–113, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1375

[10] von Schuckmann, K., and Coauthors, 2016: An imperative to monitor Earth’s energy balance. Nat. Climate Change, 6, 138–144, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2876

[11] Schwarz, M., D. Folini, S. Yang, and M. Wild, 2019: The Annual Cycle of Fractional Atmospheric Shortwave Absorption in Observations and Models: Spatial Structure, Magnitude, and Timing. J. Climate, 32, 6729–6748, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-19-0212.1

[12] Yang, S., Zhang, X., Guan, S., Zhao, W., Duan, Y., Yao, Y., … Jiang, B. (2023). A review and comparison of surface incident shortwave radiation from multiple data sources: satellite retrievals, reanalysis data and GCM simulations. International Journal of Digital Earth, 16(1), 1332–1357. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538947.2023.2198262

[13] von Schuckmann, K. and Coauthors, 2023: Heat stored in the Earth system 1960–2020: where does the energy go? Earth System Science Data, 15(4), 1675-1709, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-1675-2023