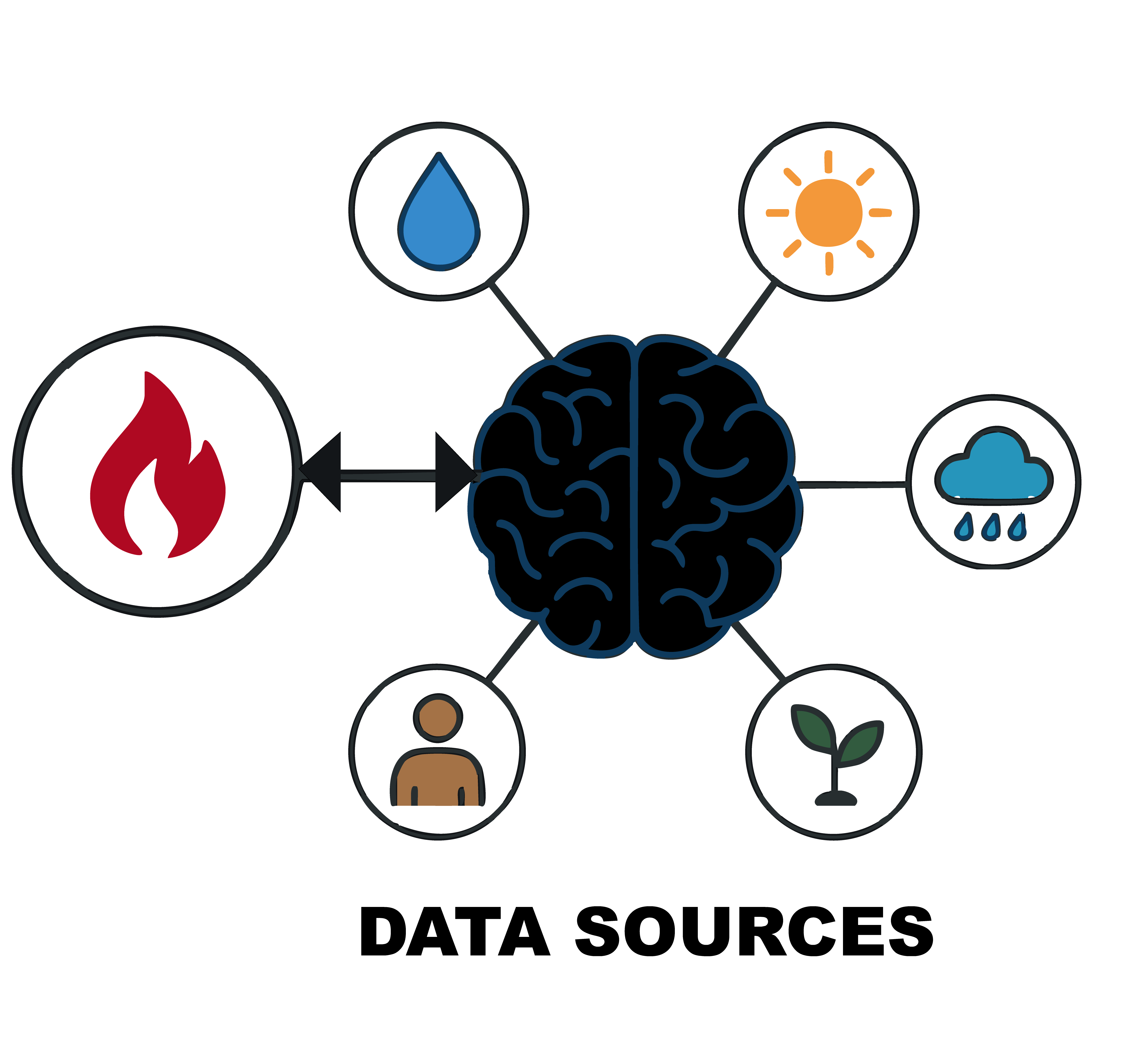

A data driven model needs data

Data sources to train the PoF

In fuel-rich environments, weather is the dominant control of fire behaviour.

To begin your data collection, we recommend focusing on four key environmental variables: temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, and wind speed. These variables represent the fundamental controls of how fire behaviour, and they are at the core of nearly all fire-weather indices used operationally around the world.

Each variable plays a distinct role in shaping landscape flammability. Temperature is one of the most immediate drivers: as temperatures rise, vegetation and soils lose moisture more quickly, and both live and dead fuels become more prone to ignition. Prolonged warm conditions can push even healthy vegetation into moisture stress, making it more combustible.

Precipitation acts in the opposite direction. It replenishes moisture in fuels and slows the drying process, reducing the likelihood that a spark will result in a fire. But precipitation also shapes fire risk over longer periods. Wet springs or wet years stimulate vegetation growth, building up large fuel loads which can later burn if drought conditions return.

Relative humidity is closely linked to fuel moisture, particularly for fine fuels like grasses and leaf litter. When the air is dry, these fuels lose moisture quickly and ignite much more easily. When humidity is higher, even small increases in atmospheric moisture can keep fine fuels from reaching the critical dryness needed to sustain fire spread. Because humidity changes rapidly over the course of a day, it introduces fast variations in fire danger. The data used here derives relative humidity by first computing the saturation vapor pressure at the air temperature and the actual vapor pressure at the dew point (both via a Clausius–Clapeyron/Magnus approximation), then taking the ratio of actual to saturation vapor pressure multiplied by 100.

Finally, wind speed is the most dynamic and often the most dangerous factor. Wind supplies oxygen to flames, drives heat into unburnt areas, and can carry embers far ahead of the main fire front, creating spot fires and accelerating spread. Strong winds can transform a small ignition into a fast-moving, intense wildfire within minutes.

Together, these four variables describe the conditions under which fires can ignite and spread. They provide a solid, intuitive foundation for understanding landscape flammability and are a suitable starting point for anyone beginning their PoF modelling journey. They also provide a data-driven alternative to the Fire Weather Index.

In absence of any other source, fuel is the most important control globally on fire activity.

To model how vegetation influences wildfire behaviour, two key aspects must be captured, how much fuel is present and how dry that fuel is.

Fuel load represents the total mass of above-ground biomass available to burn. It includes:

🌿 Foliage (live and dead) 🌳 Wood (live and dead)

We estimate fuel load by combining Satellite-derived Above-Ground Biomass (AGB) from ESA-CCI (2010 baseline), and Daily Net Ecosystem Exchange (NEE) from the ECLand land-surface model (forced by ERA5) with bias correction from atmospheric inversions.

This approach allows us to reconstruct daily biomass evolution at ~9 km resolution. AGB is then partitioned into live and dead components using vegetation-type-specific ratios and leaf area index. This gives a dynamic estimate of foliage and wood fuel loads, consistent with fire-modelling practices.

Live Fuel Moisture Content (LFMC)

💦🍃 LFMC expresses how much water is contained in living vegetation relative to its dry mass. It determines how easily plants ignite and how fast a fire can spread. We use a semi-empirical model, trained on the Globe-LFMC in-situ dataset, to estimate daily LFMC from:

🌿 Leaf Area Index (LAI)

💧 Soil moisture (root-weighted)

🌳 Vegetation type

The model ensures physically realistic moisture ranges and captures seasonal vegetation responses to drought and growth cycles.

Dead Fuel Moisture Content (DFMC)

DFMC describes the moisture content of dead leaves, litter, and woody debris—fuels that respond directly to weather. We generalize the Nelson (2000) physical model to estimate DFMC for standard dead-fuel classes (1h, 10h, 100h, 1000h). Short-lag fuels (1h, 10h), which represent dead foliage, respond to fast humidity changes. Long-lag fuels (100h, 1000h), which represent dead wood, respond to multi-day weather patterns. DFMC for foliage and wood is derived by weighting appropriate fuel classes based on vegetation type.

Road Density

Roads facilitate human access to wildland areas, increasing the likelihood of ignitions through activities such as agriculture, forestry, and recreation. However, they may also contribute to fire suppression efficiency and serve as firebreaks, creating a complex relationship between road density and fire outcomes.

The Global Roads Inventory Project (GRIP) dataset, which provides a global map of road networks at ~8 km resolution, has been regridded for use here.

Population Density

Around 90% of wildfires are human‑ignited, making human presence a useful indicator of potential fire occurrence. Fire incidence generally rises with population density but eventually saturates and at very high densities, suppression efforts typically limit the potential for large wildfires.

The data provided here are derived from the Gridded Population of the World, Version 4 (GPWv4) dataset, which provides gridded population estimates at ~1 km resolution in 5-year intervals from 2000 to 2020.

Various sensors and fire products are available for use in a PoF-style system. Here we attempt a binary classifier model, that is an indication of the probability of a fire yes/no. As such we use hotspot detections rather than burned area.

Active fire (AF) detections were taken from the MODIS MCD14ML product, which provides daily fire hotspot locations based on thermal anomalies detected at 1 km resolution. These data were gridded to coarser daily resolution and represented as binary values (1 = at least one hotspot detected, 0 = none). We applied quality assurance flags to exclude low-confidence detections and removed spurious signals when possible.

- Di Giuseppe, F., Pappenberger, F., Wetterhall, F., Krzeminski, B., Camia, A., Libertá, G., & San Miguel, J. (2016). The Potential Predictability of Fire Danger Provided by Numerical Weather Prediction. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 55(11), 2469–2491. 10.1175/jamc-d-15-0297.1

- McNorton, J., Moreno, A., Turco, M., Keune, J., & Di Giuseppe, F. (2025). Hydroclimatic Rebound Drives Extreme Fire in California’s Non‐Forested Ecosystems. Global Change Biology, 31(9). 10.1111/gcb.70481

- Di Giuseppe, F., McNorton, J., Lombardi, A., & Wetterhall, F. (2025). Global data-driven prediction of fire activity. Nature Communications, 16(1). 10.1038/s41467-025-58097-7

- McNorton, J. R., & Di Giuseppe, F. (2024). A global fuel characteristic model and dataset for wildfire prediction. Biogeosciences, 21(1), 279–300. 10.5194/bg-21-279-2024

- Agustí-Panareda, A., Massart, S., Chevallier, F., Balsamo, G., Boussetta, S., Dutra, E., & Beljaars, A. (2016). A biogenic CO 2 flux adjustment scheme for the mitigation of large-scale biases in global atmospheric CO 2 analyses and forecasts. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 16(16), 10399–10418. 10.5194/acp-16-10399-2016

- McNorton, J. R., & Di Giuseppe, F. (2024). A global fuel characteristic model and dataset for wildfire prediction. Biogeosciences, 21(1), 279–300. 10.5194/bg-21-279-2024

- Yebra, M., Scortechini, G., Badi, A., Beget, M. E., Boer, M. M., Bradstock, R., Chuvieco, E., Danson, F. M., Dennison, P., Resco de Dios, V., Di Bella, C. M., Forsyth, G., Frost, P., Garcia, M., Hamdi, A., He, B., Jolly, M., Kraaij, T., Martín, M. P., … Ustin, S. (2019). Globe-LFMC, a global plant water status database for vegetation ecophysiology and wildfire applications. Scientific Data, 6(1). 10.1038/s41597-019-0164-9

- Nelson Jr, R. M. (2000). Prediction of diurnal change in 10-h fuel stick moisture content. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 30(7), 1071–1087. 10.1139/x00-032

- Meijer, J. R., Huijbregts, M. A. J., Schotten, K. C. G. J., & Schipper, A. M. (2018). Global patterns of current and future road infrastructure. Environmental Research Letters, 13(6), 064006. 10.1088/1748-9326/aabd42

- Center For International Earth Science Information Network-CIESIN-Columbia University. (2017). Gridded Population of the World, Version 4 (GPWv4): Population Density, Revision 11. Palisades, NY: NASA Socioeconomic Data. 10.7927/H49C6VHW

- Giglio, L., Schroeder, W., & Justice, C. O. (2016). The collection 6 MODIS active fire detection algorithm and fire products. Remote Sensing of Environment, 178, 31–41. 10.1016/j.rse.2016.02.054